From the 2011 St. Paul Almanac

A grizzled old towboat mate of twenty-six named Steamboat Bill explained

the dangers of working in high water to me in very simple,

very direct terms. “Rule number-one is: Don’t fall in! If you fall in, you’re

dead. It’s that simple. The current will drag you under and you’ll drown!”

He told me this from the deck of a barge moored in South Saint Paul in

the spring of 1975, when the Mississippi River was rising fast.

Years later I watched as another young deckhand learned this lesson.

It was spring of 1992 when he slipped on an icy deck and went into the

swirling frigid water under the Lafayette Street Bridge. Two of us were

right behind him, and we dropped to our knees and looked into the dark

water but could see nothing. A second later, a gloved hand shot up, and

we grabbed him before the current could carry him away. In seconds, we

dragged him into the galley and deposited the sputtering kid on the deck

next to an electric heater. He sat there blinking a few seconds before he

could stutter, “Th-the da-damn cu-cu-current t-t-took my nu-nu-nu-new

Sorrels right off my f-f-feet.”

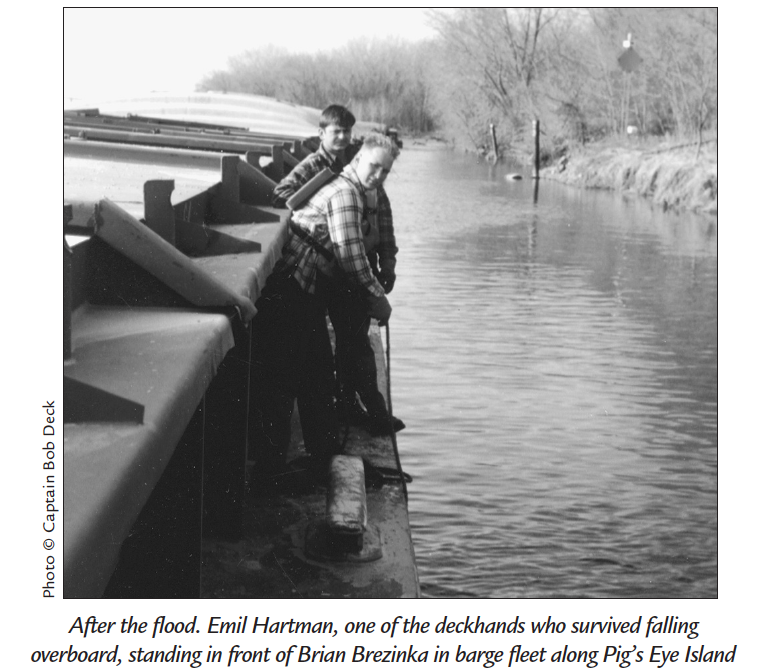

The flood of 1993 was a time of learning for river man and animal

alike. In the early morning hours of June 23, the river rose high enough to

shut down railroad bridge operations, cover Shepard Road, and swallow

up Harriet and Pig’s Eye islands. Then, half the barges fleeted in South

Saint Paul broke loose. It took several boats to chase and round them up

before they could collide with the other fleets and 494 bridge and cause

some real catastrophe.

I later spoke with a deckhand who saw the breakaway. His boat was

holding four loads that had hit the far bank when they broke loose. He

pointed at a bare tree stump on the bank. It was about eight feet across

and looked to have been torn apart. “That big cottonwood tree just exploded

when the barges hit it!” he said.

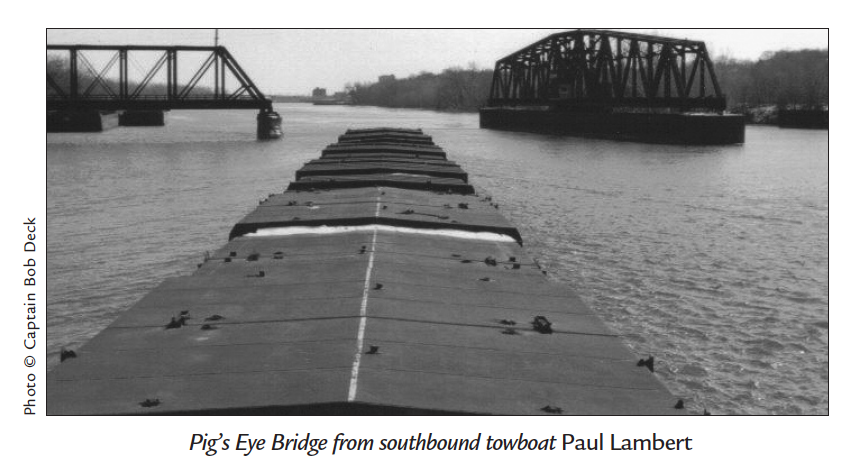

One boat was released from cleanup to return to the wharf barge in

Pig’s Eye Lake and retrieve those of us who would work the day shift. Four

crews crowded onto the Lois E as she headed back out to the river to finish

securing a couple dozen barges. The high water had created some new

hazards as the current had increased. There is a shifting sandbar across

the river from the old packing houses where the current is dammed, causing

a series of rapids or standing waves with crests as high as five feet.

I watched from the port window of Lois E’s pilothouse as the pilot

guided the boat through the first of the waves. The square bow dipped

down and sank underwater before wallowing free of the river. As the boat

pushed toward the next wave, we spotted two adult deer swimming frantically

with the current. We watched helplessly as the pair of deer tried

vainly to swim through the waves to get to us. They must have been desperate

to think our noisy towboat would save them. When they were just

a few feet away, they turned together and swam downstream away from

the boat. Fatigue must have won out, because they disappeared between

the waves and we never saw them again.

We walked the barges, surveying the broken rigging, and someone

heard a mewing sound from the island, which had become completely

submerged. The current swirled around the trees many feet over what

had been solid ground days earlier.

In between the trees, a fawn struggled to stay above water. In response

to our coaxing, it swam to the edge of the barge, but then panicked and

swam around the upper end and out into the main channel. Worried

that it would meet the same fate as its parents, we turned the boat loose,

and the pilot guided us down close to the startled fawn. I held one of the

deckhands by his belt and lowered him down as he scooped the fawn out

of the river.

While the orphaned critter wandered about the galley, we made another

round of the fleet and managed to free a family of ducks caught between

two of the barges. It took a little effort with a broomstick to nudge them up

and out of the space to where their wings could spread enough to get away

from us. Sometime during the early afternoon, a U of M agriculture team

came to pick up the fawn at our wharf barge in Pig’s Eye Lake.

Later that day, my brother Doyle, who was the mate on another boat,

was training in a green deckhand. His boat was faced up on the upstream

end of a group of loaded barges. It was time to remove the long, heavy

wires that hold the boat to the barges. Doyle was strong and knew the

technique and quickly threw one of the wires onto the hook on the bow

of the boat.

“Don’t do that by yourself!” he yelled as the new kid set about to lifting

the other side wire from the timberhead on the barge. It was a warning

that was ignored or came too late. As soon as the wire was in his hands, he

leaned back and fell onto his rear as the wire pulled him over the end of the

barge and into the wicked current. By the time Doyle got to him, he had

lost his grip on the edge of the barge and was about to slip under the fleet

to drown for sure. Doyle dove along the deck, somehow managing to hang

over the end of the barge and reach down just in time to snag the kid’s

wrist before the current could suck him under the barges. He managed to

pull the greenie out of the river and dragged him onto the barge. As they

both slumped there catching their breath, Doyle said to him, “What did I

tell you? Don’t fall in the damn river! If you do, you’re dead.”