Big River Magazine / September – October 2010

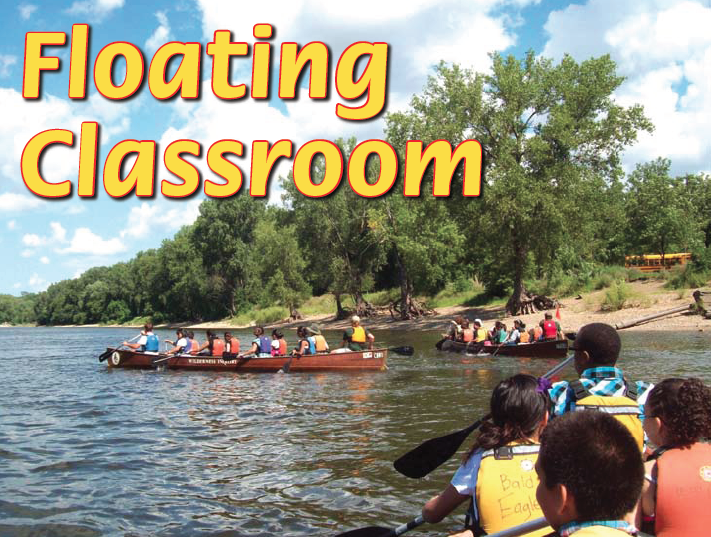

Students take off in canoes especially made for Wilderness Inquiry by

Northwest Canoe.

When the subject matter is the Mississippi River and the students live in the Twin Cities, canoes are a better teaching vehicle than desks. And, most teachers would agree that the most effective lessons engage all five senses. The Urban Wilderness Canoe Adventure (UWCA), sponsored by Wilderness Inquiry of Minneapolis and the National Park Service, puts local students on the Mississippi River in canoes, where they can find plenty of sensory input.

UWCA is the brainchild of Greg Lais, founder of Wilderness Inquiry (WI), and Dave Wiggins, a park ranger for the Mississippi National River and Recreation Area (MNRRA). Greg Lais cofounded WI back in 1978 with a mission to make it possible for people of any ability to connect with and enjoy the wild parts of our world. This newer UWCA program is an effort to extend that mission to Twin Cities youth.

On a recent Monday morning I joined park rangers and UWCA team leaders at the boat ramp at Hidden Falls Park in St. Paul to prepare for students who would soon arrive in buses from the Ramsey Arts Junior High summer school program. On today’s trip we would paddle from Hidden Falls Park to Pike Island in Ft. Snelling State Park where students would visit the Thomas C. Savage Visitor Center to gain an understanding of how European- Americans first pushed into this Northwest Territory and the impact this had on the Dakota people. The 24 foot, 10-person, voyageur-style canoes we would use were commissioned by Wilderness Inquiry and specially built by Northwest Canoe, in St. Paul’s Lowertown.

Before the 30 seventh and eighth graders could begin their transformation into voyageurs, they needed to learn about canoe safety and paddling. Each student, armed with a paddle, joined a large circle around Kellen Hoxworth, the WI staff leader.

“Hold your paddle in your right hand out to the side like this,” she demonstrated. “And then you dip your paddle into the river like so. Then pull back, and when it comes out of the water make it flat like a pizza paddle that you’ve seen the pizza guys use to pull a pizza from one of those hot ovens. So when we paddle … let’s do it now together in the air. Say to yourself ‘paddle, paddle, paddle’ and then ‘pizza, pizza, pizza.’ And try to stay together on that. Are there any questions?”

A concerned girl raised her hand. “So if someone falls in do we have to jump in and save them?”

“No, no. We keep our eyes on that person and throw them a ring buoy that is in every canoe and listen to what the canoe captain says.”

Paddling into History

If you’ve not seen groups of 12 and 13 year olds try to produce a coordinated motion, then you’ve not witnessed small-scale pandemonium. Once out on the Mississippi, the canoe captains did a wonderful job of quickly shaping these city kids into paddling teams.

Hoxworth wasn’t the only teacher. The leader of the pack in my canoe was Captain Hillary Hayssen, a Harvard English major, who on more than one occasion helped me with my grammar and syntax. (“It’s a paddle Bob, not an oar!”)

Most of the talk in the canoes concerned who was splashing who and rounds of silly jokes. When I asked some of the students how their expectations compared to what they were experiencing, the answers were short and non-committal: “I’m still waking up.” “It’s okay, I guess.” The real opinions came out in their willingness to listen to the rangers as they talked about the natural history and the interplay between cultures as white Americans expanded into Indian territory.

Dave the Voyageur (aka ranger Dave Wiggins) shared the details of his life paddling bundles of fur on the three major rivers used for transportation in this region: the Mississippi, Minnesota and St. Croix. Then Voyageur Dave pointed to the ramparts of Fort Snelling overhead and told how the fort changed the way business was done by the fur traders and how it changed his role regarding his Dakota in-laws and his white counterparts.

“You know I am a leetle old for a voyageur. Many of my old partners are dead and gone. They live maybe 30 years, and the weight of canoe and furs on portages does them in … gets to their knees or they die from the hernia.”

Ranger Mary Blitzer guided the weary voyageurs into the visitor center,near Fort Snelling, where she and Hoxworth showed them displays of wild creatures and how people affect their habitats. Ranger Kathy Swenson gathered the group inside the Dakota Memorial and talked about how Dakota people lived on Pike Island and its importance to their spirituality and livelihood. The students were beginning to show signs of understanding how each of us can change the way we interact with our world to accommodate animals and other cultures.

The students seemed to enjoy the paddle back upstream against a lazy current to Hidden Falls Park just a little bit more after learning about people who paddled the same stretch hundreds of years before. There seemed to be a little more respect for the legacy, demonstrated by their eagerness and much improved teamwork at the oars … I mean the paddles.

Teacher Katie Flaherty contacted me afterwards to share some of the students’ writing about the trip. The broad range of impressions was powerful. The teachers, too, were impressed.

“It was fun, especially since several of the girls on Monday were whining about the heat and paddling work, but when the second group of students was set to go the next day, we had many openings because we were only half the size of the usual UWCA groups. All the Monday kids asked to go again on Tuesday with that smaller group. It was pretty awesome to see that much enthusiasm from kids who had been complaining about the heat and the work of paddling up and down that stretch of the Mississippi. That first group all went again on Tuesday,” Flaherty said.

“We were doing a unit on Huck Finn. The kids all read an abridged edition and the connection with the river was tremendous. They did a writing project where the day on the river was their own personal Huck Finn experience.”

(Mostly) Fond Memories

Flaherty shared what some of the students wrote about the trip.

From a seventh-grade girl: “Well the adventure I had was on the Mississippi River. I really got the feel of the old life of the Native Americans when we were in the canoes. I really felt like I was living in their time. And imagining how much work and time they put into paddling. We went on hikes and met a French Voyageur.”

From a seventh-grade boy: “There was this great unit of people that were canoeing. When we all got in the canoe we started off last so we can test our skills. So we started paddling and the French guy started singing a song and we all had cooperation. So we passed everyone by, even the leaders with no sweat. So we hit the land with honor.”

From an ELL (English language learner) seventh-grade girl: “My canoeing adventure on the Mississippi River was great. I went to the Mississippi River with summer school. I was really excited. We were had fun. We were canoeing, paddling and walked in the woods and knew the history of the Mississippi River National Park. We were put our foot in the water and our shoes got wet. And we were took pictures and one more thing; we were found a dead fish ewwww … and it stunk. So that is the story of my canoeing adventure and that’s the memory for the first time I went to the Mississippi with my friends.”

From an ELL seventh-grade girl: “This summer school I went for canoeing with some students. I was really excited and it was really fun. I learned to paddle and it was also fun. I was really hungry but the lunch was not that tasty. It was really sunny and hot so I put my foot in the water with my shoes on. So my shoes was all wet. When I come back home my shoes stinks like death fish. All the staff was really friendly and it was a memorable day of my life.”

If these sentiments are typical, then Wilderness Inquiry’s mission to connect city youth with the wild Mississippi River has succeeded. They plan to put 7,000 urban students on the river this summer and 10,000 by 2011. That is a lofty goal but one that is so important to reclaim the connection to the river.