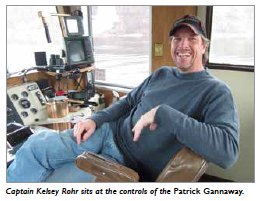

In early November, I was a guest of Captain Kelsey Rohr and his crew aboard the motor vessel Patrick Gannaway on their daily run from St. Paul to north Minneapolis. Kelsey has piloted this towboat for the last 20 years, pushing loads of sand and gravel upriver. From 1997 through 2000, I was a part of the crew. I wanted to make the run one more time before the Upper St. Anthony Lock is shut down to halt the advancement of Asian carp up the Mississippi River.

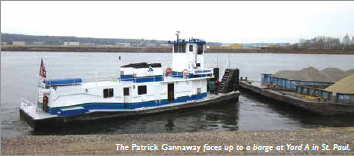

I met Kelsey, Glenn Carlson and Joe Bebeau at the boat sometime around 04:32-damn-early in the morning at Aggregate Industries Yard A. The Patrick Gannaway was moored along the sea wall across from the St. Paul airport. It was a cold, windy and very dark morning as the crew donned their insulated coveralls, fired up the boat and readied to leave the dock. By 05:00 they had faced the boat up to two barges, and we departed. Down in the galley the guys were putting their lunches away and planning their day of cleaning and maintenance, while Kelsey made his way past Dayton’s Bluff.

When I got up to the pilothouse Kelsey was negotiating his way between a line boat getting ready to head south with 12 loads and the local fleet boat Itasca. We were past downtown St. Paul and reached the confluence of the Mississippi and Minnesota rivers before we saw even a hint of daylight. As it got lighter I could see Glenn walking the tow of sand barges, checking tanks for water and stopping at the bow to make sure his lock line was ready for the first of the three locks between here and our destination.

Kelsey masterfully swung the two barges, all 400 feet of them, around Monkey Rudder Bend at Hidden Falls Park in St. Paul. Before the dam at Hastings created this pool, the old steamboat pilots brave enough to guide a boat around and through the cataracts between here and downtown Minneapolis risked everything to make this bend without shearing their rudders off on the tight turn. It isn’t a whole lot easier these days, even with the wider, deeper channel.

Soon we were past the mouth of Minnehaha Creek and into Lock 1 at the Ford Dam. The Ford plant is gone now, along with the tall iconic Ford sign that was visible for miles up and down this stretch of river.

Joe knocked the boat loose and slid up alongside of the barges. These locks are smaller than the 600-foot locks downstream. The locks up here are 400 feet, just long enough for two 200-foot-long barges. The barges are 35 feet wide and the chambers are 55 feet wide, so boats that run to Minneapolis are designed to be less than 20 feet wide, so they can fit between the barges and the wall.

The water lifted us almost 30 feet, the the level of the next pool. The upstream gates opened, and Kelsey gave the barges a little shove then worked the boat away from the side of the tow and backed up to where he could face up once again. Joe and Glenn slapped the heavy face wires onto the corner timber heads while Kelsey eased the throttles ahead.

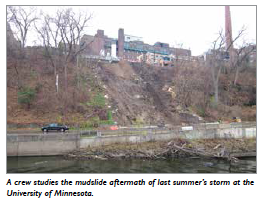

The Lower St. Anthony Falls (LSAF) Lock is about six miles upriver. We were in the “gorge,” where the river runs between steep wooded bluffs, now ablaze with fall colors. Where the wind had stripped the trees bare, you could spot abandoned summer encampments of the homeless, their tattered blue plastic tarps and cheap tents hanging limp.

The last mile below the falls passes between the eastand west-bank campuses of the University of Minnesota. We watched some foolhardy city workers on the west bank under the hospital scale the precipice where an early summer thunderstorm had washed out the bluff, exposing the foundation of one of the buildings.

Kelsey swung the tow gently around the last two hard bends to make the lock. The new hydro plant retro-fitted into the dam was creating a nasty outdraft. I have taken the Padelford boats up there, but Kelsey’s tow outweighs those boats by thousands of tons and he really had to be on guard to get into the chamber safely.

“When they first started operating that hydro we had some real problems with the set on the land wall. In fact one day they were running water so fast through the gates on the dam that we nearly stalled out halfway in. I had to shove the engines full ahead to get in the last barge length!” Kelsey recalled.

As soon as he drove out of the Lower Lock he was setting up to drive into the Upper St. Anthony Lock roughly a thousand feet ahead. The approach passes right under James J. Hill’s Stone Arch Bridge, which had one arch reconfigured to accommodate tows.

This would probably be my last transit of the Upper Lock, so I was hopping back and forth behind Kelsey taking photos through the pilothouse door of the old General Mills dock and the new cantilevered Guthrie Theater. Kelsey, ever patient with my distracting behavior, was 100 percent focused on the walls of the lock ahead, because Glenn was out there on the bow signaling him onto the wall.

Glenn later told me he doesn’t even need to signal. “Kelsey is really slick in these locks. He never even touches the wall til I am ready to catch a line.”

Kelsey pulled the twin main engines out of gear with a hiss of air from the throttles. Out on the head Glen Carlson slung his gnarled rope fender in between the barge and the lock wall to cushion the blow. But there was no blow as Kelsey handled the loads in the lock as gently as a baby.

“I’ve probably made these locks over 20,000 times, near as I can figure,” he said.

The USAF lock is the last of the three locks that complete the barge channel between St. Paul and Minneapolis’ Upper Harbor. This is the end of an era on this little stretch of the Mississippi. Glenn and Kelsey don’t have many more trips to Minneapolis. All trips will end in the fall of 2014 or the spring of 2015, when the Army Corps of Engineers closes this uppermost lock at St. Anthony Falls.

When the 2014 Water Resources bill was finally signed into law, it included a small rider to forestall the advancement of invasive Asian carp by closing the USAF lock to river traffic. This decision was a complete about-face from Minneapolis’ vision in the early half of the last century, when the city fathers worked to surpass St. Paul in every way they could.

“The Minneapolis Chamber of Commerce suggests that there is an economic necessity for a continued properly maintained nine-foot channel from St. Louis northward to a commodious upper harbor at Minneapolis; that the upper harbor will accelerate industrial activity in Minneapolis and that this in turn will result in greater prosperity throughout the entire upper Midwest,” claimed the pamphlet titled “Greater Minneapolis” published by the Minneapolis Chamber of Commerce in October 1949.

The Chamber and other river industry leaders from Minneapolis lobbied Congress long and hard to get these two locks built to achieve the title: Head of Navigation for the Mighty Mississippi River. Most of the other locks on the Upper Mississippi were built in the 1930s.

In September of 1963 the first boat to transit the Upper Lock, according to Corps historian John Anfinson, was the motor vessel Savage, owned by the former Twin City Barge and Towing Company.

Talk of closing this lock to stop a fish I’d ever even heard of provoked some pretty strong emotions in me that came as a surprise. I’m still not convinced it is the right thing to do, but I wondered why I cared so much. The Padelford excursion boats that I drive today never go that far, so why did I care?

Remembering the Early Days

I didn’t know any of this when I rode along with the late great Captain Larry Hetrick on the Mike Harris in the spring of 1975. It was my very first day on a towboat and my first time on the river. In fact it was the first time I ever saw the river. He took two empty barges from South St. Paul up through those three locks to the Riverside Power Plant’s coal dock above Lowry Avenue at the head of navigation.

Later, when I was a deckhand for Larry, one of my duties was to fill out a Corps of Engineers form declaring our tow size, type and tonnage. This was part of a deal to justify those locks and deflect criticism.

We were still filling out these “lock tickets” when I learned to run the locks as a greenhorn pilot on the “Tall” Paul Lambert. Boats that ran to the Minneapolis Upper Harbor could hydraulically raise and lower wheelhouses to duck under low bridges around the locks. I can still remember the way my knees went rubbery the first time I had to drive into that lock chamber with two loaded barges and the water was rushing across the entrance trying to pull the tow over the spillway.

On busy days as many as five or six boats locked through well into the 1980s. After the Lambert, I drove the Sophie Rose pushing coal loads out of Riverside down through the locks and around to the Black Dog power plant on the Minnesota River. Then when I worked for Bob Draine’s Capitol Barge, I would haul grain, fertilizer, molasses and salt with the Mike Harris and Lois E.

Perhaps my emotional reaction to closing the lock has something to do with my upbringing as the son of an Air Force fighter pilot, bouncing around the country from base to base. Every year I went to a new school in a new place. The idea of a hometown was a concept that escaped me. When Dad retired, he moved the family to St. Paul and flew a lot of odd jobs. One job was flying for Jack Lambert of Twin City Barge. A couple of years later, he and mom were divorcing as I entered my senior year of high school. He was fixing to fly the coop, but before he left he offered to get me a job on the TCB towboats. Since then this little bit of the Upper Mississippi has become my home and those locks were a big part of that home, beginning with that first ride with Capt. Hetrick.

Last Ride

Soon Kelsey and the boys had the northbound and loads spotted at the dock below Lowry Avenue. After Glenn walked out onto the empties and fine-tuned the loose coupling left by the dock men, Joe threw a line around the port tow knee and we were southbound. Kelsey snaked the empties away from the dock and twisted around to face up in a few quick minutes. These guys work together like a well oiled a machine.

I made an effort to see everything from the dock on down through the nasty turn at the Great Northern RR Bridge, since I might never see it from a boat again. A few geese lingered along the shoreline getting ready to fly south for the winter. It brought to mind a cold fall night 15 years ago.

Glenn and I were standing on the bow of maybe these same empty barges, and the moon cast a ghostly shadow over the river. We were looking down at the Great Northern bridge watching Kelsey get ready to slide under it while timing the “duck” on his hydraulic pilothouse. Between Broadway Avenue and the railroad bridge thousands of migrating geese floated in the still water. As the front barge cleaved through that still water, the bow wave became half water and half feathers. The geese about to be run over would take flight and land just ahead of the tow. The next ones about to go under would hopscotch over them and land just beyond.

Once Kelsey cleared Great Northern I made sure to take several photos of my all time favorite landmark on the river: the old Grain Belt sign that looms over De La Salle High School on Nicollet Island. It used to be quite a sight for me as a deckhand riding the head through the big city — all lit up on those lonely cold nights. It has been turned off for years, but recently the August Schell Brewing Co. purchased it and plan to relight it!

It probably seems strange that a grown man can be so nostalgic about a huge slime and scum covered cement box, but I spent a lot of time in that box and it played a sizable role in much of my growth as a man and a river pilot. Oh sure I can always head over to Minneapolis and walk around, maybe stand out on the Hill Bridge and look at the cement spillway, but it is not the same as staring down into the curved long wall and steering into the chamber with an outdraft and knowing that this view requires a special kind of skill and knowledge.